Note

This post was originally on the MIT Admissions website as a guest blogpost. If you want, you can read it on the MIT Admission site here.Protochess.com

How to write a chess engine in 6 months.

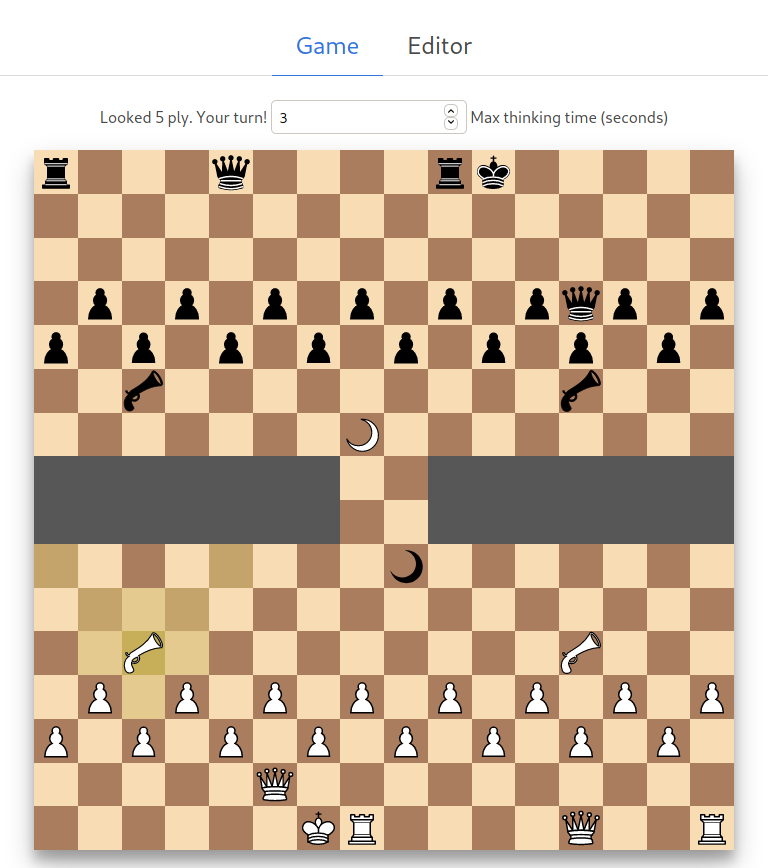

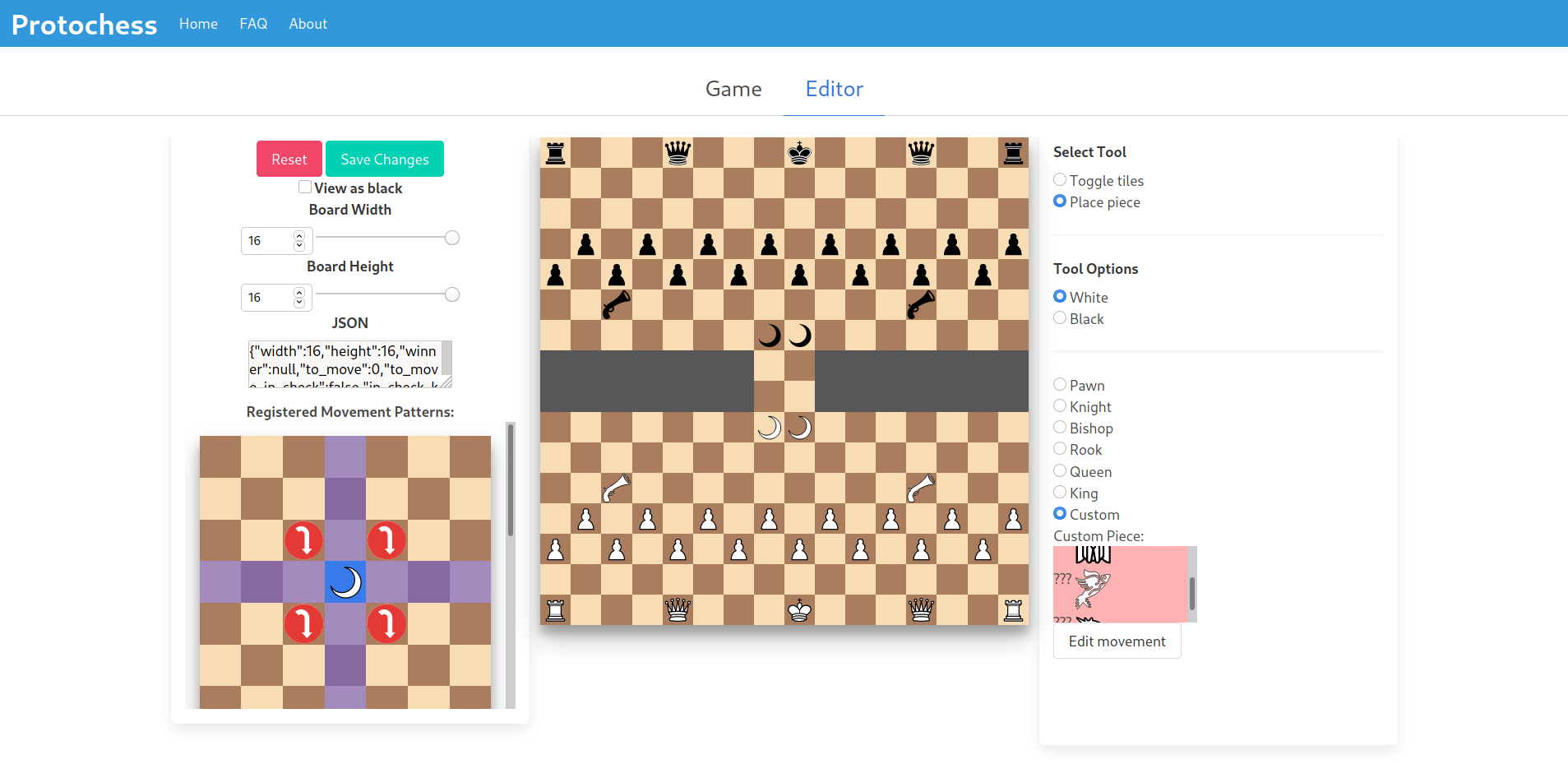

TLDR: I made this chess website that lets you design custom pieces and boards. Play on it here. You can play against the chess engine I wrote as well.

The Inspiration

CPW. 2019. I was a but a lowly prefrosh making friends. I met Chambers. You might’ve heard of him. He’s that guy from the Duolingo thing.

He challenged me to a game of chess. Aidan Chambers, the chess man. He was born from chess. Years of generational chess experience flows through his veins. Me? Raymond Tran? I haven’t played chess in years. Yet there I was, ready to challenge the one and only Aidan Chambers. Long story short he made some terrible mistake and I won.

This didn’t phase me. But I know it hurt him. From this he would never recover. His chess confidence was destroyed. I broke him that day.

Now he won’t stop talking about chess. Like a broken record. Since then, he’s been training his chess ability. Little does he know: so have I.

For the past six months I have been secretly training in chess with hopes to beat Aidan Chambers yet again. During this time, I learned about the existence of chess variants: chess games with modified pieces and boards. I couldn’t find a website that let you build these yourself, so I did what any rational person would: devote the next six months of my life to writing a chess variant website.

This blogpost is the story of how I wrote that website. Play on it here. The story of me vs Chambers in our ultimate chess battle? That story is to be continued….

Engine

Behind every good chess website is a chess engine. This is the program that determines the rules behind chess and which moves are the best for any given board. Chess engines usually work by searching through all possible moves and picking the best one (the newer, machine-learning based chess engines are the exception). This sounds simple, and it is! Modern chess engines just use a lot of optimizations to be able to search deeper into the game tree.

Sidenote: I think 6.172 makes you write a chess engine for a chess variant called Leiserchess, but I haven’t taken that class yet so I could be wrong. I imagine a lot of the techniques I’m about to describe are also used in that class.

Anyway:

What goes into a (basic) chess engine?

Board Representation

Note: Protochess supports up to 16×16 sized boards and custom pieces that do crazy things, but for the purposes of this article I’ll be writing as if it were just a standard chess game. I will include a few sentences on where protochess differs in the approach, though.

The first step to writing your own chess program is picking a way to represent your board. A natural approach would be something like this:

let board = [

'r', 'n', 'b', 'q', 'k', 'b', 'n', 'r',

'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P',

'R', 'N', 'B', 'Q', 'K', 'B', 'N', 'R',

];A single array, with a character for each piece. Upper case for white, lowercase for black. This is called a square-centric approach, since we keep information based on the squares on the board.

Cool, but a little too slow for our purposes. Remember: it’s essential that we do everything as fast as possible to have a good engine.

We can use a trick! Computers are really good at doing math with 64 bit integers. 64 just happens to be the number of squares on a standard chess board! Funny coincidence. Knowing this, we can represent our pieces like this:

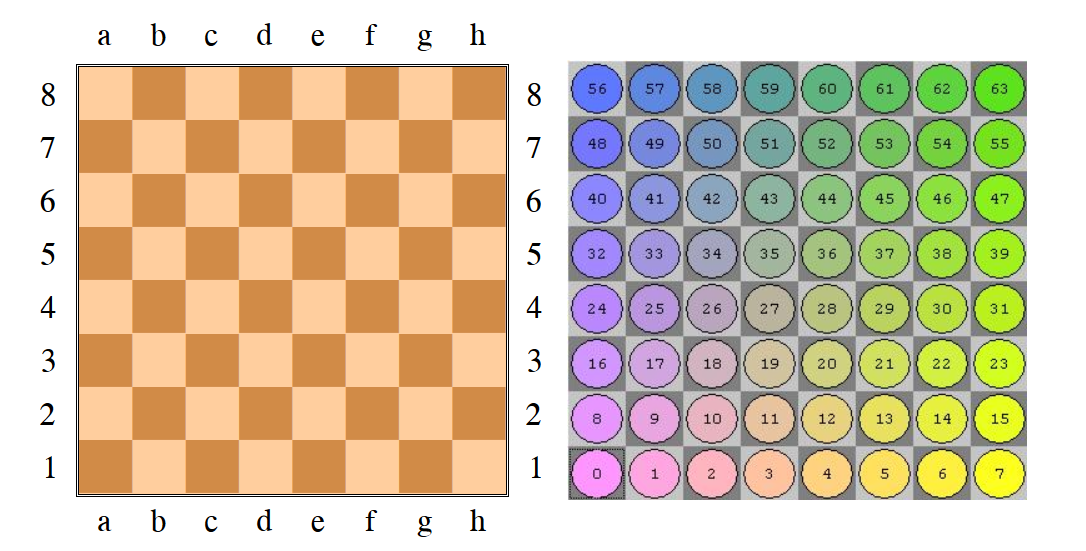

Let’s call each 64 bit number a bitboard. A bitboard is just a mapping from bits in the number to places on the board. We can do this in a number of ways, but in protochess this is done using little-endian rank-file mapping. It looks like this:

Notice that the 0th bit is on the A1 square, and the 63rd bit is on the H8 square.

We can represent the a board using one bitboard per piece type. We will have 12 in total (one for each piece type and color == 2x pawn, 2x knight, 2x king, 2x queen, 2x rook, 2x bishop)

In each bitboard, set the bit to 1 if the piece is there, and 0 if the piece isn’t.

For instance, if our board looks like this:

'r', 'n', 'b', 'q', 'k', 'b', 'n', 'r',

'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p', 'p',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ', ' ',

'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P', 'P',

'R', 'N', 'B', 'Q', 'K', 'B', 'N', 'R',The corresponding bitboard for the white pawns looks like this:

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

00000000

11111111

00000000Pretty simple huh? In contrast to the earlier array-based design, this is a piece-centric approach, since we focus on each piece type as a set of locations.

We have a few advantages here, especially when you consider bitwise operations that computers can do.

One of them is the AND (&): let c = (a & b) takes two numbers a, b, and returns a new number c where each bit in c is true if the corresponding bits in a and b are true.

Using this representation, we can perform really powerful set-wise operations, such as asking “give me all the white pawns standing on the second rank.” In our array representation, we’d have to search through 8 indices, while now, we can write (WHITE_PAWNS & 2ND_RANK).

Move Generation

This is the game of chess itself, with all its moves and rules. While it’s simple in theory, it is actually the hardest part about writing an (efficient) chess engine.

In chess, there are two types of pieces: jumping pieces and sliding pieces. Jumping pieces like the knight can “jump” over other pieces, while sliding pieces like the queen can have their movement blocked. Move generation for sliding and jumping pieces can be done very efficiently using bitboards.

Jumping pieces (knight, pawn, king)

The fastest way to generate moves for any piece is to just look up the possible moves in a precomputed table. For jumping pieces, this is easy since we don’t have to consider any blockers in the way.

At the start of our program, we initialize a huge table for jumping pieces (like the knight), mapping board locations (indices) to possible movements (as a Bitboard). We can use bit manipulation (bit shifts, masks) to set bits in the relevant locations for each jumping piece table.

Then, during our program, we can access the movement by indexing the table. For instance, a knight sitting at C3 can be indexed like this:

let moves = KNIGHT_TABLE[C3]

// which gives you:

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. 1 . 1 . . . .

1 . . . 1 . . .

. . x . . . . .

1 . . . 1 . . .

. 1 . 1 . . . .(For clarity, . is used instead of 0 and the C3 square is marked with an x instead of 0).

It’s important to remember that these are just possible squares that we can move to. We don’t want to attack our own pieces, for instance. This is where our choice of bitboards really shines. We can “block out” invalid moves like attacking your own pieces with simple bitwise operations, like so:

//All moves, including attacking our own pieces

let moves = KNIGHT_TABLE[C3]

//Moves, but only the ones that don't attack our own team

moves &= !MY_PIECES //Notice the use of the AND and NOT operatorsWith a few adjustments, it’s easy to see how the scheme above works for all jumping pieces (kings, pawns).

Sliding pieces

Sliding pieces are a little more complicated. It is possible to use a similar approach as jumping pieces, but we would need a lot of memory and a few tricks (See: magic bitboards. Protochess, with it’s focus on having 16×16 sized customizable boards would need a LOT of memory.

So instead, let’s think about what you really need to determine the possible moves for a sliding piece.

The direction (north, west, east, south, etc)

The pieces in the way (we’ll call them blockers)This is the minimum amount of information that we need to determine moves. For a standard chess game, we have up to 2^8 possible occupancies, which looks something like this:

00000000, 00000001, 00000010, ..... 11111111We can actually loop through all possible occupancy states like so:

for i in 0..256 {

let state = i;

...

}..and precalculate sliding moves for each state! We can store our results in a table like so:

SLIDING_MOVES[index][occupancy] = 00111100All we need now is a way to map each direction (rank, file, diagonal, antidiagonal) to and from the relevant 8 bits. We can use the first rank as a place to extract our relevant bits from the bitboard.

Say we have a rook on C3 (marked as x) and we want to know where it can go (looking at only the horizontal direction), given the blockers on the board (marked as 1):

let bitboard =

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . 1

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . 1 .

1 . x . 1 1 . .

. . . . . . . .

1 . . . . . . .//Shift the bitboard down to the first rank (8 bits per rank)

bitboard = bitboard >> 2 * 8

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . 1

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . 1 .

1 . x . 1 1 . .// Remove everything that is not on the first rank

bitboard = bitboard & FIRST_RANK

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

1 . x . 1 1 . .Now we can use the bits at the first rank to index into our table:

SLIDING_MOVES[2][10001100b] = 11011000

//2 is the x index with our mapping

//10001100b represents the bits at the first rank

//11011000 is the precalculated sliding moves…And we can map these 8 bits onto the first rank of a bitboard and shift it back up using the same operations in reverse, giving us:

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

1 1 x 1 1 . . .

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .…which are the possible moves for our rook on C3! Hooray!

Similar operations can be done to map between diagonals and the first rank. Again, we need to mask off this bitboard the same way we did earlier to ensure that we don’t attack our own pieces.

We’re still missing one key aspect: How do we get our moves “out” of a bitboard?

Simple, just loop through them like so:

let movelist = []

let from_index = /* some piece location */

let moves_bitboard = KNIGHT_TABLE[from_index]

while moves_bitboard != 0 {

let to_index = moves_bitboard.lowest_one();

//Compiled languages can do this very efficiently with intrinsics

movelist.push(new Move(from_index, to_index))

moves_bitboard.set_bit(from_index, false)

}Apart from the standard rules like encoding how all the pieces move, you also have to consider rules such as the en-passant, castling, and promotions, but these don’t have any fancy tricks like above so I won’t mention it.

Testing your move generation

Question: How do you make sure your move generation is correct? There are so many possible moves, with so many possible boards and responses?

Answer: Use perft! This is a function that you write into your chess engine that walks through the game tree, move by move, and recursively counts through all possible moves up to a certain depth. It looks like:

fn perft(int depth){

let nodes = 0;

if depth == 0 {

return 1;

}

for move in generate_moves(board){

board.makeMove(move);

nodes += perft(depth - 1);

board.undoMove();

}

return nodes;

}For example, perft(0) on the starting position gives us 20, since there are 20 possible moves white can make (2 per pawn, 2 per knight). perft(1) = 40, since the sides are symmetric.

Here are some more perft values at the starting position:

depth nodes

0 1

1 20

2 400

3 8,902

4 197,281

5 4,865,609

6 119,060,324

7 3,195,901,860

8 84,998,978,956Don’t you just love exponential growth? Chess actually has a branching factor of around 35, meaning there are more possible chess positions (10^120) than atoms in the universe (10^81).

Writing a good move generator legitimately took me months (mostly because I didn’t know what I was doing yet). I ended up rewriting this several times, unsatisfied with the performance of each. The first couple tries were in C++, and my time for perft(6) was 5+ minutes on my computer. This was because of a slow move generation algorithm–math instead of lookup tables, and because I was using a slow 256 bit number library (big boards big challenges big thoughts).

I eventually settled on a final rewrite in Rust, using a faster 256 bit number library and the generation scheme described above, which is providing me with decent speed and efficiency. Perft(6) on the starting position finishes in less than three seconds now. Much better!

Evaluation

Evaluation is the process of assigning the board a score. It allows the engine to determine what a “good” position means. The score itself is the sum of the player to move’s material score and positional score.

The material score is just the amount of material that either side has. Protochess measures material in centipawns, which is 1/100ths of a pawn. Using this model, here are the centipawn values for each standard piece:

// Scores are in centipawns

const KING_SCORE:isize = 9999;

const QUEEN_SCORE:isize = 900;

const ROOK_SCORE:isize = 500;

const BISHOP_SCORE:isize = 350;

const KNIGHT_SCORE:isize = 300;

const PAWN_SCORE:isize = 100;

const CHECKMATED_SCORE:isize = -99999;

const CASTLING_BONUS:isize = 400;As you can see, we add a bonus for castling moves, while getting checkmated essentially means having -INF score. This works fine for the pieces in a standard chess game, but the whole point of protochess is to design your own pieces, so how do we score those?

At the moment, the score for each custom piece is determined as the sum of possible moves that each piece has. For instance, if a piece can move north and south, the score for that piece is simply [northScore + southScore].

The other part of the evaluation score is the positional score. Having more pieces than your opponent is important, but so is where those pieces are. It wouldn’t be very good to have all your pieces stuck behind your pawns (called piece development). Normal engines handle this by defining piece-square tables, which are big arrays mapping each tile to a certain point value for each piece.

Here is an example table for white pawns taken from the chess programming wiki:

// pawn

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

50, 50, 50, 50, 50, 50, 50, 50,

10, 10, 20, 30, 30, 20, 10, 10,

5, 5, 10, 25, 25, 10, 5, 5,

0, 0, 0, 20, 20, 0, 0, 0,

5, -5, -10, 0, 0,-10, -5, 5,

5, 10, 10,-20,-20, 10, 10, 5,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0As you can see, pawns are encouraged to stay in the middle and progress towards the 7th/8th rank so that they can promote.

This works fine for normal chess, but again protochess is designed to not be normal chess. We can design custom boards of up to 16×16 tiles, so pre-set piece square tables won’t be very useful here. To get around this, piece square tables are generated dynamically for each piece by counting the possible number of moves for each piece on an otherwise empty board. This retains some properties like encouraging pieces to move towards the center (since pieces typically have more moves at the center), but it misses when you try to add things like king safety and pawn structure.

At the moment, this seems to be good enough to beat your casual chess player, but improvements can definitely be made.

Search

Now on to the “AI” part of the chess engine. Despite the name, it really isn’t very intelligent. Computers are just dumb rocks that we’ve fooled into doing math.

Here’s how it works:

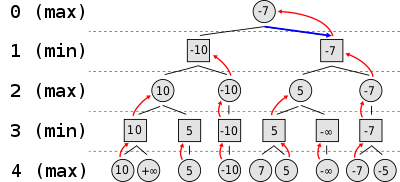

At its core the search is a highly optimized version of the minimax algorithm. This algorithm walks through the game tree up to a certain depth, assuming that each player plays optimally. It picks the branch that provides the most benefit to us, while minimizing the benefit of the opposing player.

Here’s a simplified diagram of that behavior:

Here is that framework applied in a negamax version, which takes advantage of the fact that if black is up by 5 points, then the overall evaluation is just -1 * 5 (hence the name Nega(tive)-(min)max).

int negaMax( int depth ) {

if ( depth == 0 ) return evaluate();

int max = -oo;

for ( all moves) {

score = -negaMax( depth - 1 );

if( score > max )

max = score;

}

return max;

}Now, if you were to build a chess algorithm using a plain min/max with no optimizations, it would still play decent chess, but would likely only be able to search up to 3 ply (3 moves ahead) in a reasonable amount of time. In comparison, the protochess engine currently searches to around 10 ply in ~5s on my machine. For reference, Stockfish regularly searches to 20+ ply using even more optimizations.

Here’s a list of search optimizations that the protochess engine includes:

- Alpha-beta pruning

- The idea here is to stop searching moves that automatically lead to a bad position. This is similar to how humans play chess; if we see a move that immedietely leads to a lost position, we naturally stop searching moves that come after it.

- Alpha-beta pruning alone guarantees the same end results as min/max, just with less work done.

- It’s easy to see how if we search better moves first, we are more likely to find a good variation that results in more cutoffs. So much so, that with perfect move ordering, if minmax searches x nodes, then we can expect an alpha-beta search to search only sqrt(x) nodes!

- Quiescence search

- Searches can suffer from the horizon effect, which happens when a search reaches its maximum depth but still doesn’t know enough about a position to accurately rate its moves. For instance, at the last depth of a search the engine can find a move that appears good but actually leads to the Queen being lost. To fix this, we simply switch to a Quiescence search (quiet search), meaning we keep searching using only capture moves until we run out of capture moves to make. This solves our problem of dropping pieces and results in a much more reliable engine.

- Principal Variation Search

- This search method takes advantage of the fact that it’s easier to prove a move is bad than it is to calculate the full score of a move, so we search the first moves in our list fully, and reduce the search window for subsequent searches.

- MVV-LVA Move ordering

- This stands for most-valuable-victim, least-valuable-attacker move ordering. As described above, alpha beta search benefits massively from a good search order. MVV-LVA sorts the moves in each ply to help ensure a good ordering.

- Killer + History Heuristic

- These heuristics store moves that caused cutoffs in the past, and whenever the engine encounters them again, the moves are ranked higher in the move ordering.

- Null move pruning

- Most of the time, the worst thing you can do in chess is to pass (with some exceptions). As such, null move pruning makes a “null move” (skips turn), and if the engine still can’t find a move that improves the opponent score (beta cutoff), then we know we can ignore the branch.

- Late move reductions

- Since our move ordering is pretty good at this point, we can search later moves with reduced depth. This can dramatically improve search depth, but care must be taken to ensure that our search still remains stable.

- Transposition table with Zobrist Hashing

- A zobrist hash is a number assigned to a particular board position. It is used similarly to an ID; it is supposed to be unique to the position. – These numbers are used to index a big hashtable of positions, where we store information between searches.

- Iterative deepening

- Iterative deepening just means that if we want to search to depth x, we first search to depth 1, then 2, then 3, then 4, up to x. At first glance, it may seem like doing a lot of extra work, but in reality the amount of time to search at lower depths is trivial, and it allows us to use information from the shallow searches to help us for our deeper searches (move ordering/transposition table). Additionally, we can stop early and use our low-depth results if we run out of time.

Online Play, Website, and Deployment

Now for the website itself.

The frontend was originally written using React, but after watching this video on svelte and seeing how simple it was, I switched immediately. Svelte has the added benefit of being a compiler, so the website only serves what it needs (without a virtual DOM). This basically means it should load pretty quickly, which fits the theme of this blog post quite well. I used the Bulma css library to get things looking pretty.

The backend also uses Rust, for no other reason than it seeming like the simplest solution to run our chess logic and webserver using the same language. Looking back, it would’ve been easier to use something like node.js with neon for rust bindings.

Since the engine is written in Rust, we can implement singleplayer by simply compiling our code to WebAssembly and serving our .wasm file as a static asset, without any extra work! WebAssembly is super cool; it lets you run low level code at almost native speed on the web!

As for multiplayer, websockets allow for two-way communication between the server and client, enabling features such as realtime chat.

The whole setup is hosted on DigitalOcean using their free $100 signup credit, with SSL certs from cloudflare.

Time Sink

So this project ended up taking waaaay longer than I thought it would. I expected a month max, but it turns out chess engines are really complicated.

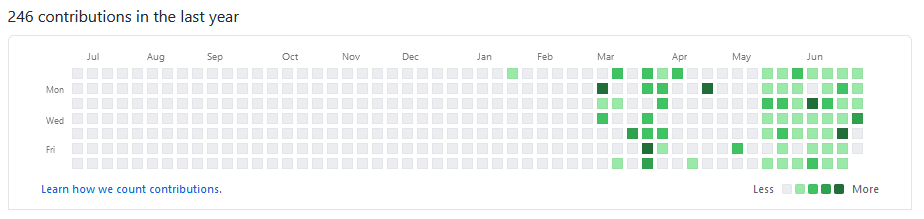

Here is a screenshot of my git history:

As you can see, I started this project in early March, and just barely finished in July. I had no idea what I was getting into, but in the end I’m happy with how it came out. I rewrote the chess engine ~3 times, each time using more advanced chess-engine-specific techniques.

There are still a lot of features that would be nice to have, but it’s definitely a usable product.

Nice-to-have-but-not-implemented list:

- Account system

- Game history

- Pre-set maps/pieces

Sidenote: Sometime during the semester, while I was at the gym with Aiden Padilla (not to be confused with Aidan Chambers, the chess boy), between our mindless Spongebob quotes that we spew between sets, we made an agreement that I’d finish the website and that he’d finish his e-bike project by the end of the semester, or else we’d owe each other $5. Well I think between the coronavirus situation and him moving out to Washington, we both failed that challenge. (@Padilla wheres the e-bike tho)

What is protochess?

I’m glad you asked, Chambers. You aren’t ready for this one.

You might’ve had years of training with your grandfather, but I have 6 months worth of training by myself most of that time programming instead of playing chess. Message me when you’re ready.

The bigger picture

There’s something really satisfying about writing a program that beats you in your own game. Recently I watched the AlphaGo documentary with Cami, and it’s absolutely incredible. These professional Go players devote their entire lives to improving at the game, which for a long time was considered impossible to write good engines for. That is until AlphaGo came and beat the number one Go player in the world, Lee Sedol.

And that documentary was about an event that happened four years ago! Now, not only have the AlphaGo team beaten themselves with AlphaGo Zero, similar tech is being used to identify diseases, develop self-driving cars, and change how we do things in almost every field.

Sometimes that change isn’t always good, though. I think it’s easy for those within tech to focus solely on the advancement of technology without considering the ethical consequences of their work. Take for instance the case of Robert Julian-Borchak Williams, who was wrongfully accused for a felony because of the implicit biases within facial recognition technology (which, by the way, is really accurate for white people but not so much minorities). I’m sure none of the engineers behind the technology wanted to target minorities, but the intent doesn’t change the outcome. Without proper auditing of the datasets that we’re using, mistakes like these are bound to happen. (Yes, even to MIT.)

It’s all fun and games making the computer go beep boop until someone gets hurt.

Along the same lines, as consumers of technology we should be mindful of the data that tech companies collect and what they do with it. It’s no surprise that companies sell your data for profit, but I find that most of us don’t know the extent of what they record and what they don’t. TikTok was recently caught recording users’ clipboard information without consent, among other previous security concerns. This is just one company — how many more are there?

You know how it can be harder to write a paper when you have someone sitting behind you watching you type every word? That happens digitally too. Being under constant surveillance can and will hinder your ability for creative thought.

But maybe you don’t care. You have nothing to hide, and the TikTok dances are pretty cool so you want to keep watching them.

What if these companies start asking for more? What if a health insurance company saw that you watched a lot of TV, so they decide to raise your rates because your inactive lifestyle puts you at greater risk for health problems? No, nevermind, you’re right that’ll never happen.

Maybe it is all just harmless advertising. For now.

But just because it isn’t happening to you right now, doesn’t mean it can’t happen.

There’s a lot more to say about this but here are some closing thoughts: Be a little more mindful of the technology that you use and especially the privacy policies behind them. Do you really need to have TikTok installed?

…Also, play on my chess website :)